I highly recommend the Jewish Museum’s The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt. It’s at the museum through August 10, 2025. I learned a lot. Turns out the book of Esther was popular during that era, in the 1600s. She is not only a heroine in the Jewish tradition, but also for Christians.

In the 1600s, immigrant Jews living in the Netherlands had religious freedom and could celebrate Purim more openly than they could in previous homelands (Portugal, Spain, Central/Eastern Europe). The exhibit explained that this holiday became symbolic of freedom and of the Jewish presence in Amsterdam.

The Dutch saw their own story in Esther’s bravery, given their newly won independence from Spain. The Netherlands gained independence from Spain in teh mid 1600s after the Eighty Years’ War. Through this, they gained religious freedom, giving safe haven to others as well, and that included Sephardic Jewish immigrants. Those immigrants sometimes came from converse families, those forced to convert to Catholicism in Spain and Portugal. The immigrants also included Ashkenazi Jews from Central/Eastern Europe.

The Dutch used the Book of Esther as an allegory for their own national identity. Haman was Cathollic Spain. Esther and Mordechai were the brave and triumphant Dutch. Amsterdam was Jerusalem. Rembrandt helped reinterpret the Esther story for the Dutch people, and the artists, Rembrandt included, used the story in paintings, etchings, plays, and home goods.

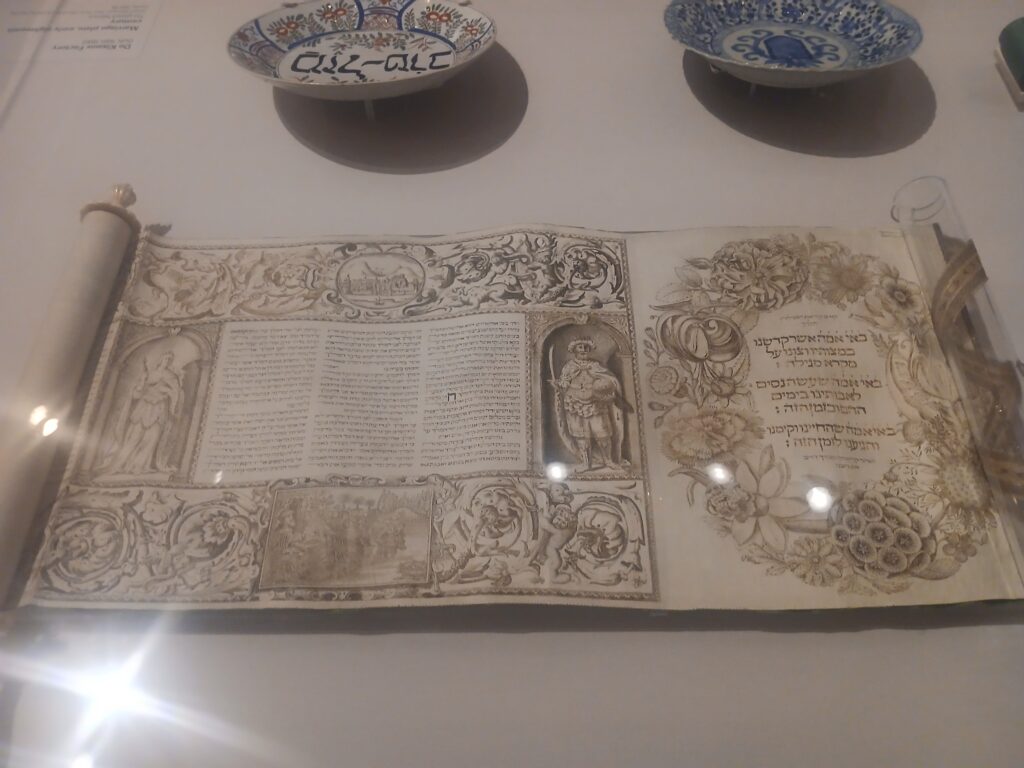

This Esther scroll is one of many from Salom Italia, an artist born in Italy and living in Amsterdam. This is from the 1640s with a printed border and handwritten text and ink on parchment. In the arches are the characters from the Book of Esther. Above are Dutch cityscapes There are a lot of his megillot in the exhibit.

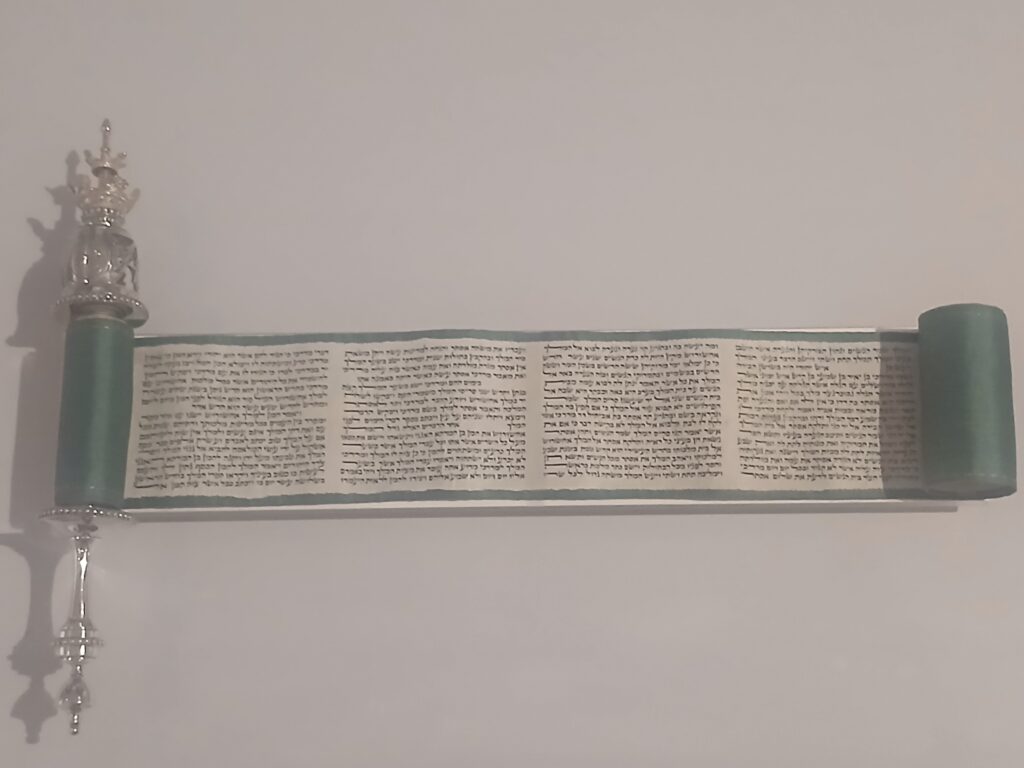

The scroll, or megillah, tells the story of Esther, which takes place after the Jewish people were exiled from Israel by the Babylonian conquest in 587 BCE. The story takes place in Susa (Shushan), Persia. That area is now Shush, Iran. King Ahasuerus rules 127 provinces stretching from India to Nubia.

Featured above are two synagogues from the early 1700s, the Sephardic Portuguese Synagogue (left) and the Ashkenazic Great Synagogue (right). Most Jewish immigrants settled in Vlooienburg, alongside Rembrandt and a diverse community.

The Ashkenazic Jews were mostly poor and secluded themselves, while the Sephardic Jews integrated better culturally and were more affluent. Jews in Amsterdam did not have to wear identifying badges or distinctive markings, as they did in other parts of Europe. They also did not have to live in a Jewish ghetto, as in Italy and Frankfurt.

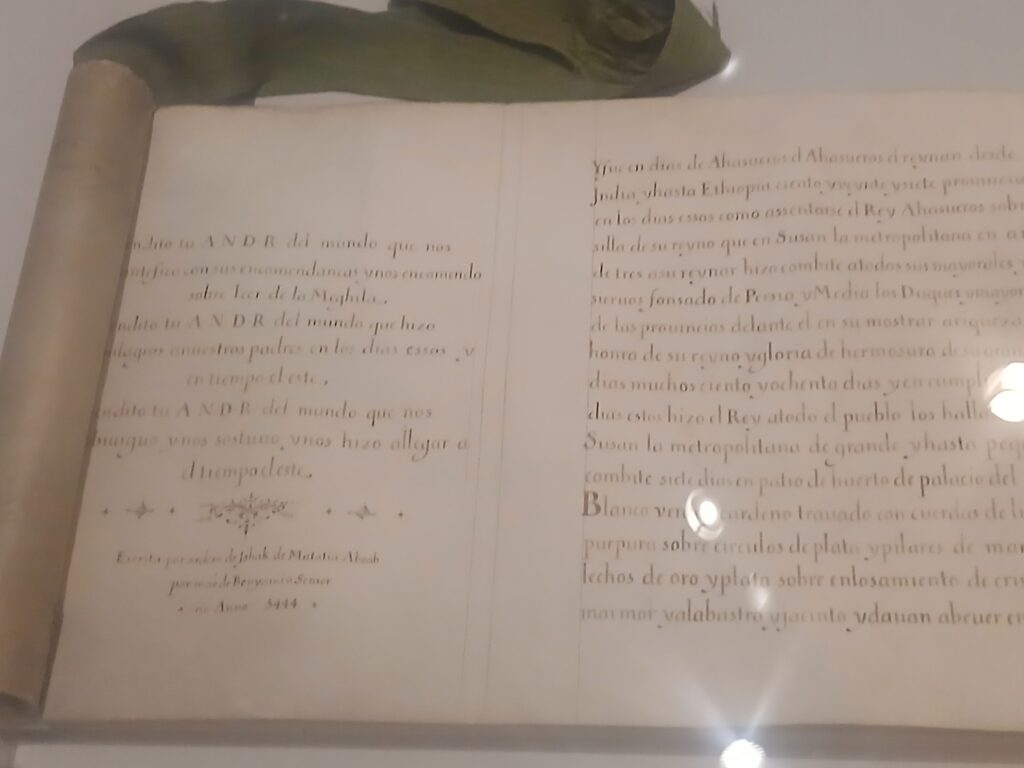

The scroll above was by a prominent Jewish artist and scribe. His illustrations include animals, cityscapes, flowers and story vignettes. He was a first-generation Portuguese immigrant.

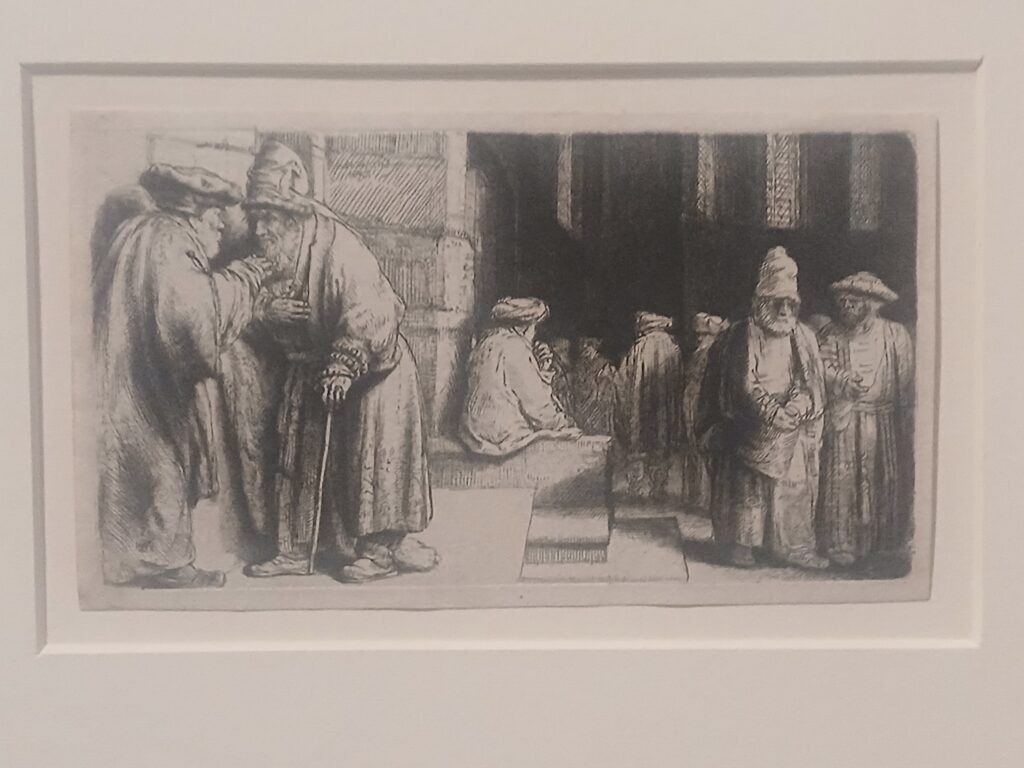

Not the Book of Esther, but an imagined scene from Temple times. Rembrandt lives in a neighborhood with many Jews, and may have encountered men looking like this in the ‘hood. Funny enough, I saw this etching and the Great Jewish Bride at a Rembrandt exhibit at the Worcester Art Museum in 2023, though those were both owned by the Worcester museum.

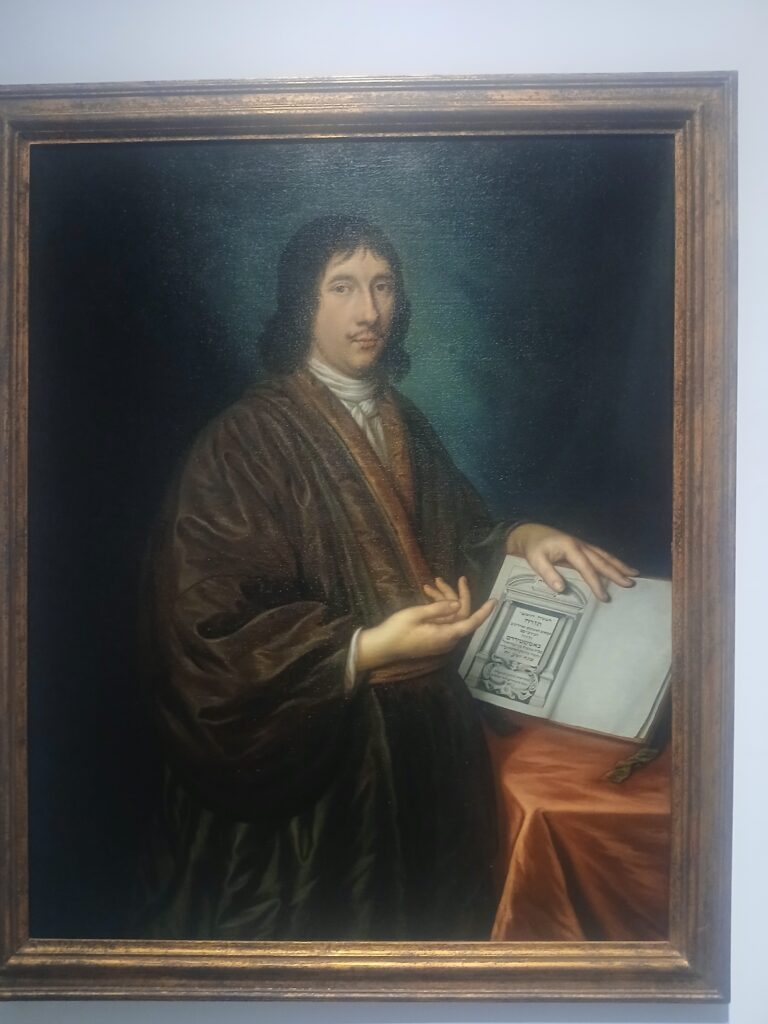

What’s interesting about the painting above is that it’s of a Dutch preacher and it highlights interest in newly printed Hebrew Bibles for Dutch Protestants. Amsterdam was becoming a center of publishing, and a Hebrew bible was becoming a symbol of status, wealth and knowledge. This edition featured in the painting was one published in 1635 by Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel, who founded the first Hebrew printing press in Amsterdam, and lived by Rembrandt.

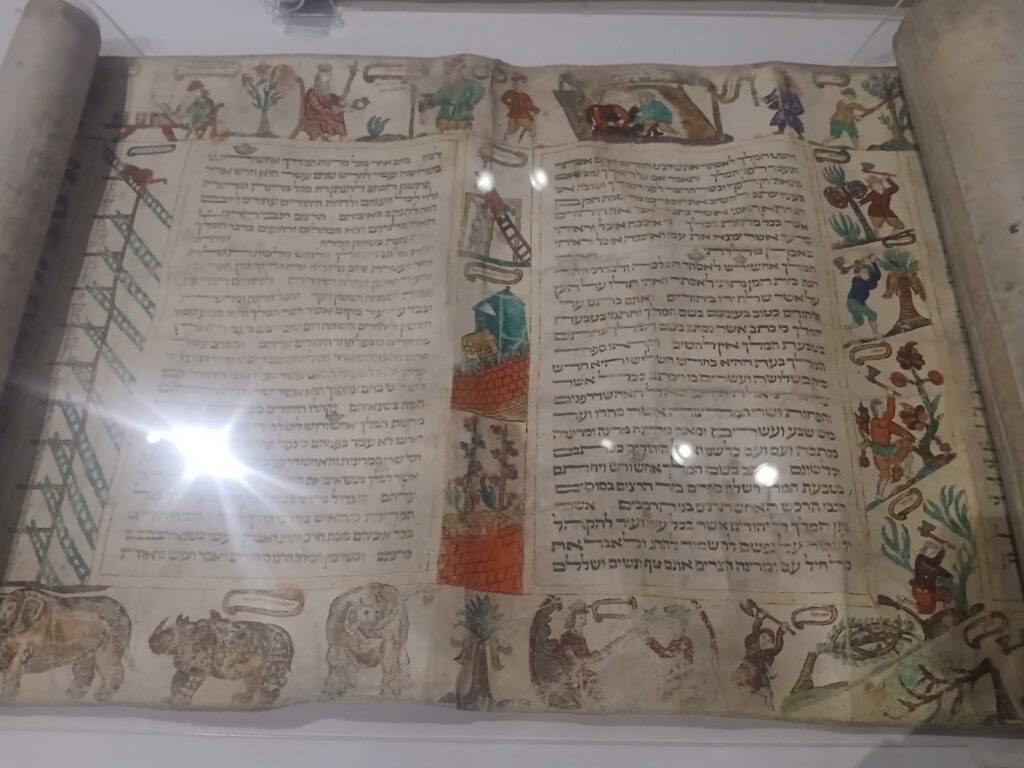

The scroll below is from 1630-40 from an unknown Dutch or German artist. It features scenes from the Esther story, but also scenes surrounded by flora and fauna not part of the European scene, e.g. rhinos and elephants, as well as palm trees. This was an acknowledgement of Amsterdamn’s trade hub status.

Two galleries held a number of paintings of the banquet scenes. There were several from Jan Steen, including the one below, which shows the king’s anger at learning that Haman’s plot was to kill all the Jews, which would include the queen.

The last room talked about the history of theater in Amsterdam, and that the Book of Esther was a popular theme.

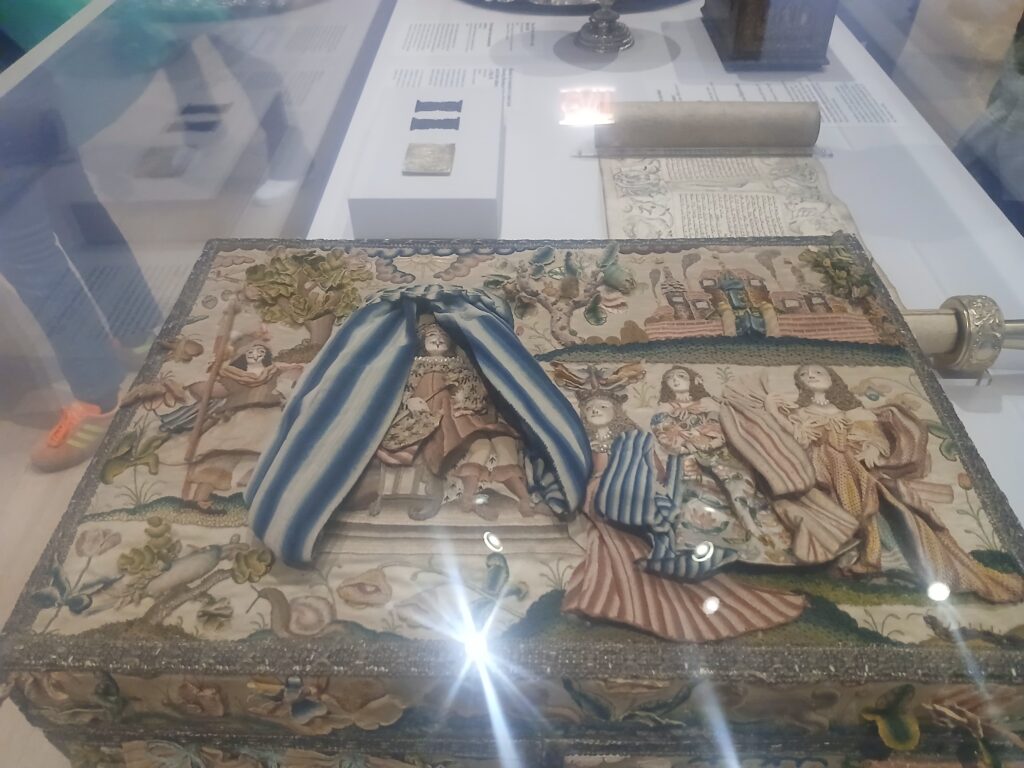

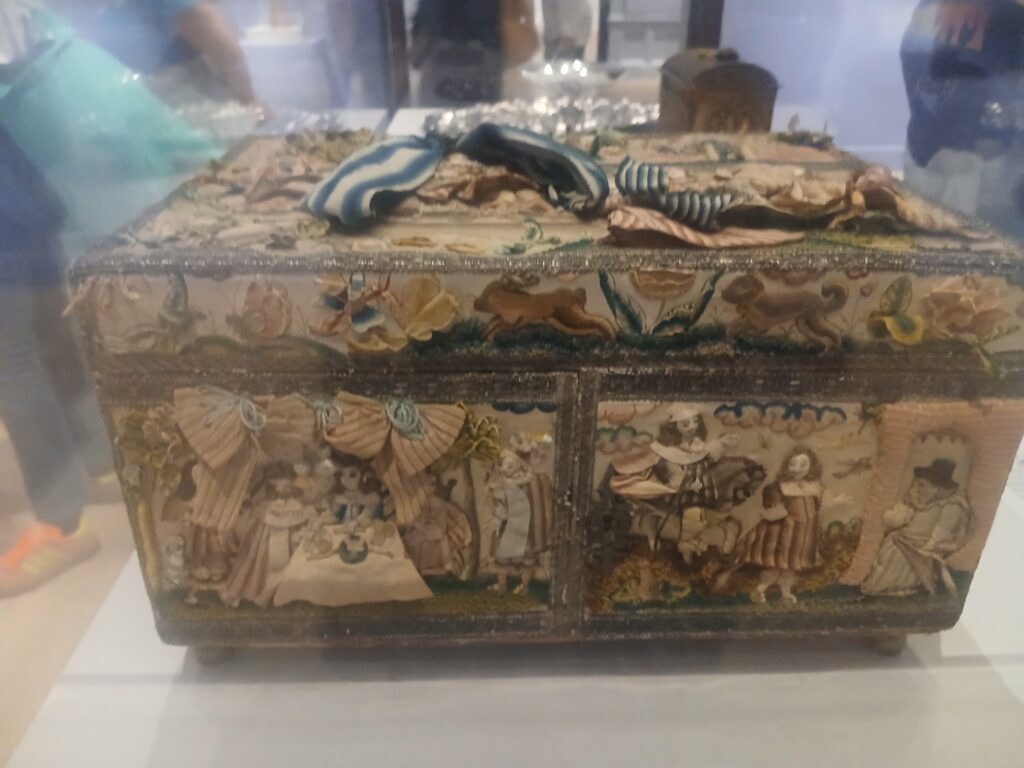

There was also a display and discussion of dowries and lotteries in the Netherlands. “Purim” means “lots” – with Haman casting lots to determine the date to kill the Jews. In the Netherlands, even today, a public lottery is held on Purim at the Portuguese synagogue. They have a charitable society called the Dotar , which awards doweries to orphaned brides-to-be. The Sephardic Jews established the society in 1616 after escaping the Portuguese Inquisition, and they still award dowries to eligible women. They had letters from some of the applicants and bowls used to draw the lots.

If you go

The Jewish Museum is at 92nd Street and 5th Avenue. They have different family programs including concerts – check before you go. They also have kid-friendly gallery guides. They have museum/exhibit tours, again check the calendar. I used the Bloomberg Connects app to get my own tour (no cost). That might be a good way for kids to explore.